The Church Book of Old Meeting House Congregational Church

By Dr Joel Halcomb

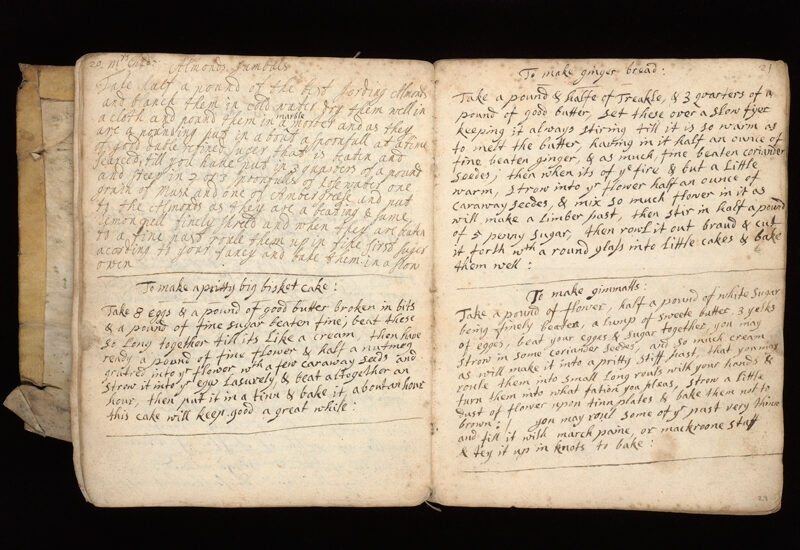

On 4 March 1974 the Norfolk Record Office received a donation of the historical records of Norwich’s Old Meeting Congregational Church. Within this donation was Old Meeting’s original ‘church book’ (Norfolk Record Office, FC 19/1). This folio-sized, leather bound volume contains the records of the church’s meetings, its admission and baptismal registers, and its correspondence, from the church’s founding in 1644 up to 1839 (with a gap between 1681 and 1782).

The Old Meeting church book is one of the oldest set of non-conformist records in the country, and one of only a handful of surviving non-conformists church books to contain records from the civil war period. While Old Meeting itself first gathered itself into church fellowship until June 1644, its origins are earlier. The founding members of Old Meeting had been followers of William Bridge, the puritan minister of St Peter Hungate and St George Tombland in Norwich during the 1630s. Bridge was forced out of Norwich by Bishop Matthew Wren in 1636 and the following year he wrote a letter to the godly of Norwich and Great Yarmouth inviting them to join him in Rotterdam for the free worship of the gospel. At the start of the civil wars these godly exiles returned to Norwich and Great Yarmouth and formed a congregational church that served both places. In the spring of 1644, under pressure from inhabitants in both places, the church decided to split. The original church remained in Great Yarmouth and its members from Norwich were dismissed to gather their own church.

The original scribe for the Old Meeting church book copied out the early records from the Great Yarmouth church book (Norfolk Record Office, FC31/1). These early entries include: a narrative of the church’s origin beginning with Wren’s episcopate in the 1630s; the foundation of the original joint Norwich-Yarmouth church and its covenant; the correspondence and accounts of the meetings that led to the establishment of Old Meeting; and Old Meeting’s original ‘covenant’. Thereafter Old Meeting’s church book becomes a rich running compilation of the church’s early history.

Old Meeting did not gain its first minister until 1647, when Timothy Armitage accepted a call to be pastor. Armitage was a recent graduate of St Catherine’s College, Cambridge and had been curate of St Michael Coslany in Norwich in November 1643. Once Armitage accepted his call in July 1647 the church quickly began to organize its affairs. Their first celebration of the Lord’s Supper took place on 28 November 1647; they soon organized monthly communion services. In January 1648 they decided that baptisms should take place on Sundays, after the sermon. In August 1648 they organized a collection for the poor members of the congregation. In August 1649 they ‘judged fitt that the ordinance of singing psalmes be exercised in publicke’. Armitage decided on the ‘vulgar translation’ that was most agreeable to the original Hebrew, and psalms were ‘to be used at the hearing of the word’.

Between the gathering of the church in 1644 and the calling of Armitage the church book only records the admission of new members. Filling the pastor’s office allowed the church to fully organize its religious services. Daniel Bradford, one of the church’s founding members, described this period after Armitage’s arrival as the ‘settling’ of the church. The church book certain bears this out.

Throughout the 1650s the church became a semi-official city church: it met in the parish church of St George Tombland and its second pastor, Thomas Allen, was granted the tithed living of St George’s by the city. The Cromwellian period therefore granted the church a remarkable freedom of public worship, but with that freedom came the challenges of religious turmoil and theological change of the ‘puritan revolution’.

Throughout the 1650s the church book contains a number of disciplinary cases typical of the time period. Throughout the summer of 1650 the church dealt with two of its young female women who were reading scandalous ‘ranter’ texts, abstaining from church services, and cavorting with ‘scandalous and profane’ people. (For more on this case, see: http://dissent.hypotheses.org/1412).

In March 1657 the church hosted a gathering of messengers from congregational churches across Norfolk and Suffolk ‘concerning the visible reigne of Christ and our duty towards the Governments of the world.’ From 1649 some congregationalists, baptists, and presbyterians claimed that the execution of Charles I represented the fall of the forth monarchy prophesized in Daniel. To help bring about the fifth and final monarchy of Christ they advocated England being ruled by ‘saints’. This ‘Fifth Monarchy’ movement was highly critical of Oliver Cromwell and his Protectorate, which they saw as preventing the rule of saints. The meeting of March 1657 pitched leading congregationalists in the Norwich and Great Yarmouth churches against Fifth Monarchists within the congregational churches of North Walsham, Bury St Edmunds, and elsewhere. The result of the meeting, recorded in the Yarmouth church book, agreed that there would be ‘in the latter dayes a glorious & vissible kingdom of Christ wherein the Saints should rule’ but by general vote the messengers decreed ‘that it was our Dutie to give subjection [to the present powers], and if any should doe otherwise it should be a matter of grief & great offence unto them.’ This judgment was then publicized to the nation at large in the government-run newsbook Mercurius Politicus.

In another dramatic case, John Lawrence became the first member lost to the Quaker movement. Lawrence was a captain in the New Model Army and joined the church in 1646. In early 1655 Lawrence was converted to Quakerism by the then young Quaker evangelist George Whitehead. After a series of attempts to reclaim Lawrence, the church finally ‘withdrew communion’ from him after a very public disciplinary hearing that lead to a riot within the city. While the church book doesn’t record the aftermath of the hearing, the memoirs of Whitehead, published in 1725, provided his own side of the story.

Interestingly, while the church book provides a running register of those admitted to membership, it provides no register of baptisms for the early period. The first recorded baptisms date from December 1657, but an entry records that they were copied into the church book at a later date from the registers of baptisms kept by Thomas Allen (sadly this register has not survived).

At the restoration the church book’s entries become sparse for a decade, before picking up again in frequency at the end of the 1660s. This is typical of most congregational records during the Restoration.

The Old Meeting church book provides a remarkable picture into the foundation and early years of one of England’s first congregational churches. It is an invaluable source for scholars interested in the Old Meeting Congregational Church and the history of early religious dissent. That it survives at all is a testament to the members of the church throughout the centuries in their determination to preserve and protect their history.

Further reading:

Browne, J., The History of Congregationalism and Memorials of the Churches in Norfolk and Suffolk (1877).

Cozens-Hardy, Basil, ‘Old Meeting House, Norwich, and Great Yarmouth Independent Church: Observations on their origins’, Norfolk Record Society, 22 (1951), 1-5.

Halcomb, J. ‘A social history of congregational religious practice during the puritan revolution’, PhD thesis (Cambridge, 2010).

LISTEN TO TALKS RELATED TO THE OLD MEETING HOUSE

Listen to Dr. Joel Halcomb's Talk on the History of the Old Meeting

Listen to Dr. Joel Halcomb Speaking on St. Georges Tombland & The Origins of The Old Meeting House Church